We have been taught to believe that blood is the ultimate anchor—a biological destiny that holds fast even when the world gives way. Yet, for the Black diaspora, history has often been the story of that anchor being violently uprooted. From the auction block to the contemporary migrant trail, colonial modernity has systematically weaponized biological lineage, shattering families to maintain state control. When the traditional house is burned down by external forces, a new way of belonging must be forged from the ashes. In these spaces of rupture, the biblical account of Mark 3:31–35 has emerged not as an ancient relic, but as a "theological grammar for survival." It offers a script for building a home when bloodlines are no longer enough to guarantee safety.

Family as a "Grammar of Survival," Not Just a Feeling

For Black diasporic communities, kinship has long been a "battleground" where colonial powers sought to control bodies by dictating who belonged to whom. This was achieved through what Sylvia Wynter calls "sociogeny"—the colonial invention of race as a genealogical hierarchy that tied human worth to "pure" bloodlines and state-sanctioned descent. By weaponizing biology, the empire attempted to render the marginalized "kinless." In response, these communities turned to Mark 3 as a "reusable category" for reconfiguration, shifting the definition of family from "descent" to "obedience."

"Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother" (Mk 3:35).

This shift was a revolutionary act of resistance. By prioritizing divine obedience over biological necessity, marginalized groups created a "charter for chosen kinship." This allowed them to reclaim their humanity in environments where their biological ties were legally ignored, establishing a logic where shared praxis and spiritual alignment create a bond more durable than DNA.

The Radical Subversion of the Imperial "Oikos"

To grasp the political threat of Jesus’s words, we must understand the Roman oikos (household). In the ancient world, the household was the engine of empire. The paterfamilias held absolute authority over his kin, mirroring the Emperor’s role as the "father of the fatherland." Biological lineage was the mechanism that secured property, maintained social hierarchy, and ensured loyalty to the state.

When Jesus refused to prioritize his biological mother and brothers who stood "outside," he was committing a profound act of "epistemic disobedience." He was not merely being dismissive; he was destabilizing the idea that loyalty must be tied to land, property, and state-sanctioned lineage. In doing so, he enunciated a "third space" of belonging. This is where African "Eldest Brother" Christologies find their power: viewing Jesus not as a distant deity, but as the mediator and protector who reconfigures the communal family around divine justice rather than imperial blood.

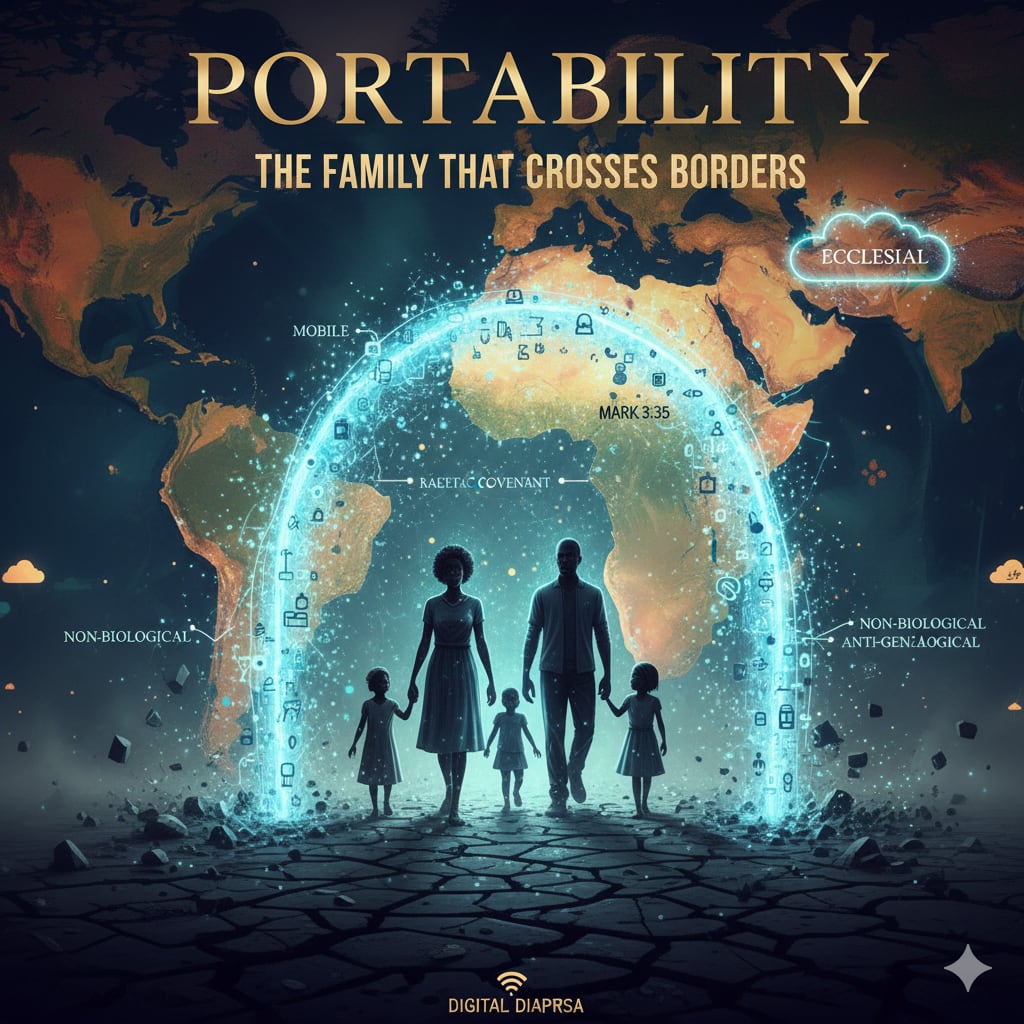

Portability—The Family That Crosses Borders

One of the most vital aspects of this redefined kinship is its "portability." Unlike traditional family structures tied to specific territories or ancestral lands, the "Transdiasporic Covenant" is designed for movement. It is a structure intended for refugees, migrants, and those in exile who cannot rely on national or territorial kinship for protection.

A transdiasporic covenant is defined by five specific attributes:

- Non-biological: It acknowledges blood ties but prioritizes bonds that transcend them when rupture occurs.

- Obedience-rooted: Membership is defined by shared ethical action and divine will, not by genealogical descent.

- Mobile: It is a structure that travels across national boundaries, maintaining coherence even in displacement.

- Anti-genealogical: It refuses the "genealogical nationalism" that ties human rights and worth to ancestry or "purity."

- Ecclesial: It creates a community accountable to a divine logic of justice rather than state-dictated boundaries.

From the Caribbean to South Africa—Comparative Snapshots of Resistance

These theological concepts are not abstract; they are the bedrock of real-world survival across the globe. Following the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean, for instance, freed people faced continued fragmentation. They responded by forming "church families" where baptismal rituals and "othermothering" networks replaced biological ties strained by the plantation system.

In the post-Windrush era in Britain, Caribbean migrants encountered a "hostile environment" that marginalized their extended family structures. As theologian Robert Beckford has observed, Black British Pentecostal churches became crucibles for "covenantal" kinship—functioning as surrogate families where "church mothers" offered nurturing and "brothers and sisters" provided the economic reciprocity the state denied them.

Similarly, in post-apartheid South Africa, queer Christian communities use this logic to navigate "queer exile." When rejected by biological families or state structures that still cling to colonial bio-essentialism, they invoke the philosophy of ubuntu—relational personhood—to form chosen families. Here, "doing the will of God" means practicing a radical inclusion that affirms the body while subverting the patriarchal lineage once used to justify apartheid.

Queer Exile as the Ultimate Theological Litmus Test

The "Queer Stakes" of this kinship logic reveal the true heart of the Gospel. For LGBTQ+ individuals, "chosen family" is rarely a lifestyle choice; it is a necessity for physical and emotional survival. However, this isn't merely a "pastoral exception" for those in crisis. Rather, queer kinship is perhaps the clearest disclosure of the Gospel’s core logic: that belonging is rooted in covenant, not biology.

The refusal of queer belonging within the church is often framed as a defense of "traditional values." Yet, from a decolonial perspective, such a refusal is actually a reinstatement of the imperial oikos. By insisting on biological or heteronormative descent as the primary marker of belonging, the church reverts to the very imperial logic that Jesus subverted. Queer kinship practices are the primary site where the radical, non-biological love of God is most clearly enacted.

The Digital Diaspora—Kinship in the Cloud

In our contemporary moment, this "grammar of survival" has moved into digital spaces. For those navigating transnational precarity—such as LGBTQ+ Christians in Nigeria who face state criminalization—online networks have become "theological shelters." These are not merely chat rooms; they are digital "maroon enclaves" where the displaced find recognition and ritual.

While the medium has changed, the underlying "covenantal logic" remains a potent strategy against the nation-state. This digital diaspora represents an anti-national ecclesiology: a kinship that exists beyond the reach of state borders and the limitations of biology, anchored instead in a shared commitment to a higher justice.

Conclusion: The Threshold of the Global Church

The global church currently stands at a critical threshold. It faces a choice: it can either continue to be complicit in "imperial kinship logics"—those of bio-essentialism, nationalism, and the weaponization of the nuclear family—or it can adopt a "decolonial ecclesiology."

The history of the Black diaspora shows that when blood and borders fail, the covenant remains. The church is called to be more than a social club for the "intact" family; it is called to be the portable family of God, capable of holding the refugee, the exile, and the rejected. The question for us is one of courage:

In a world of increasing displacement, are we brave enough to claim a family that travels beyond borders and blood?