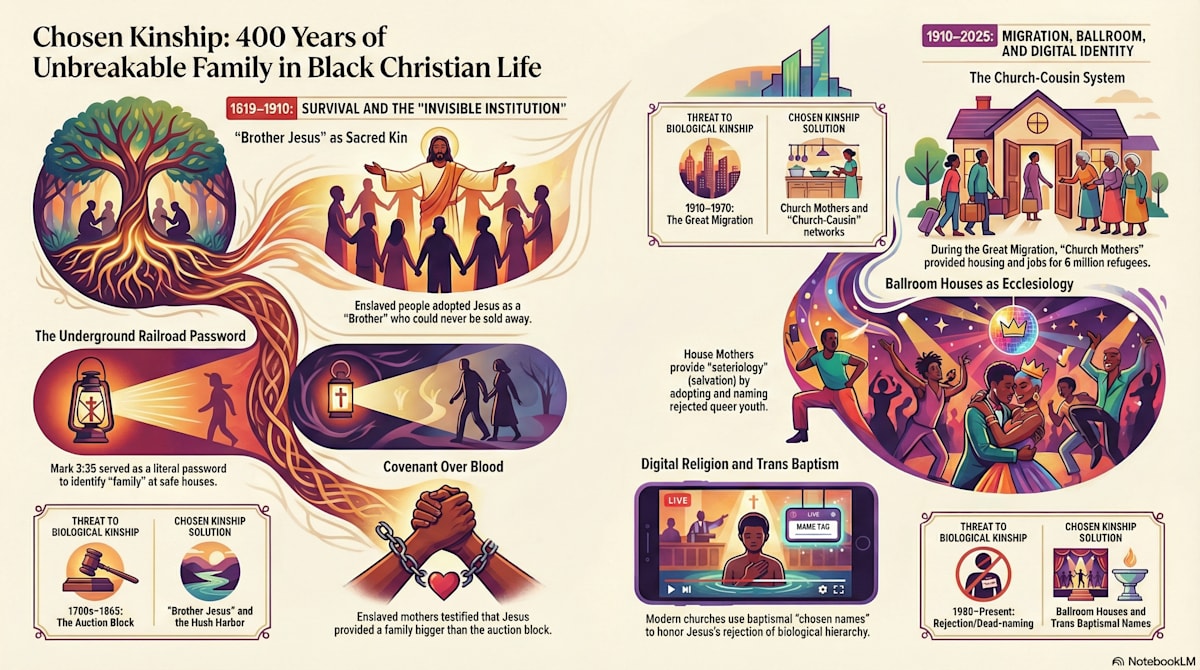

On May 12, 1723, a Virginia plantation overseer made a clinical entry into a ledger that remains a testament to the calculated cruelty of empire: “Woman Phillis delivered of twins. One sold to Carolina trader. Mother screamed so hard she had to be whipped silent.” In the logic of the slave block, biological "blood" was a liability, a commodity to be severed and traded for liquid capital. Yet, the source context tells us that night, in the damp sanctuary of a hush harbor, Phillis stood and offered a different testimony. She spoke of a Jesus who promised her a family "bigger than the devil can ever break." This was the birth of a 400-year theological tradition, a lived hermeneutic that transformed the fragility of biological kinship into the unbreakable armor of chosen family.

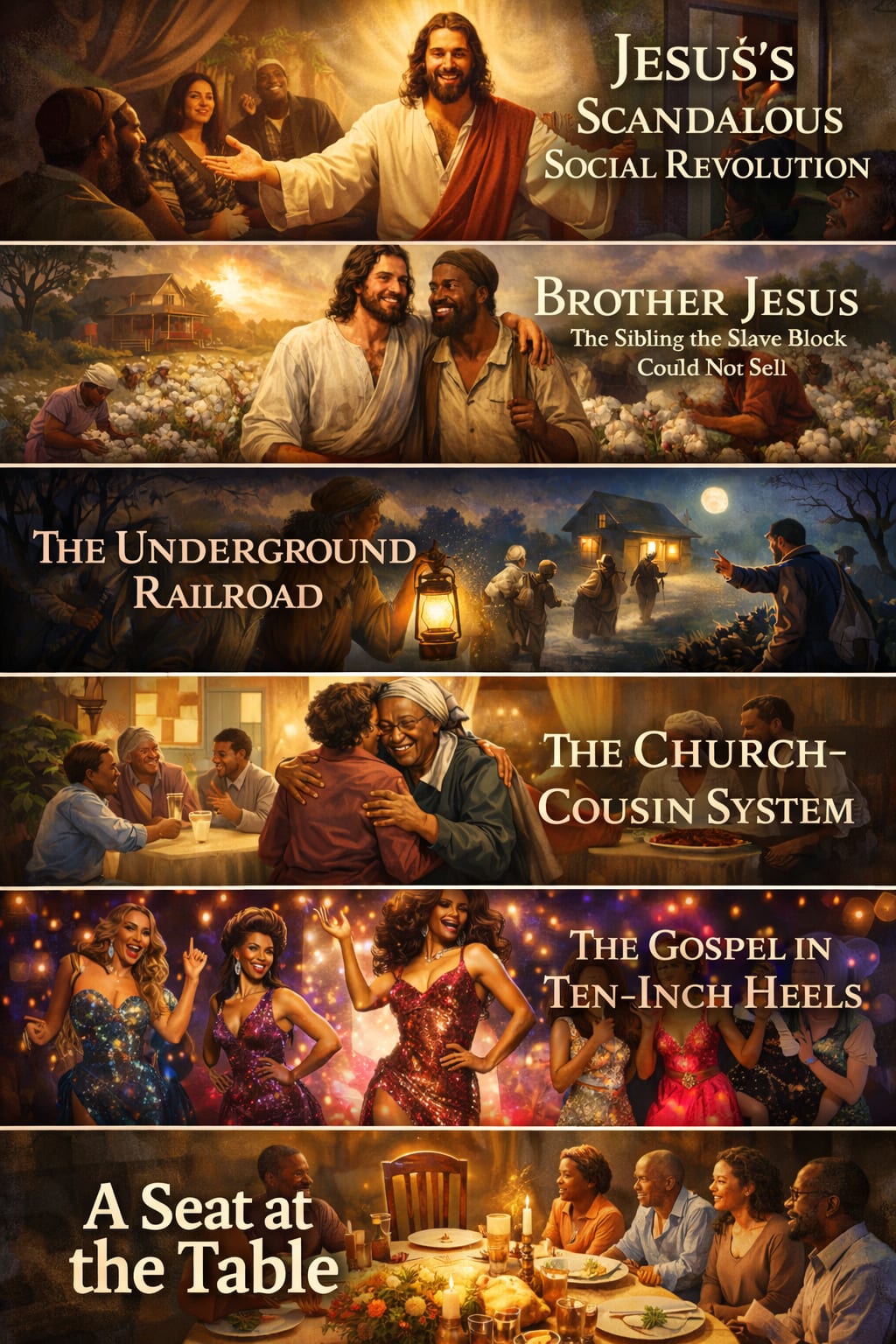

Jesus’s Scandalous Social Revolution

The theological foundation for this survival strategy is rooted in the "scandal" of Mark 3:31–35. In the ancient Mediterranean world, the oikos (household) was the ultimate source of identity, economic safety, and social location. To be rejected by one’s biological kin was to suffer "social death." When Jesus’s family arrived to "restrain" him—using the Greek verb kratēsai, which carries the weight of a coercive, legal arrest—they were attempting to save him from the social suicide of his radical ministry. Jesus’s response was a shattering of the patriarchal order:

“Who are my mother and my brothers?” And looking at those who sat around him, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.” (Mark 3:33-35)

By replacing pedigree with practice and biology with covenant obedience, Jesus enacted a social revolution. This new structure intentionally omitted the word "father," a radical challenge to the paterfamilias that protected the unique paternity of God and signaled a non-hierarchical, egalitarian community. For those whom the empire had made kinless, this text became a charter for a new kind of belonging.

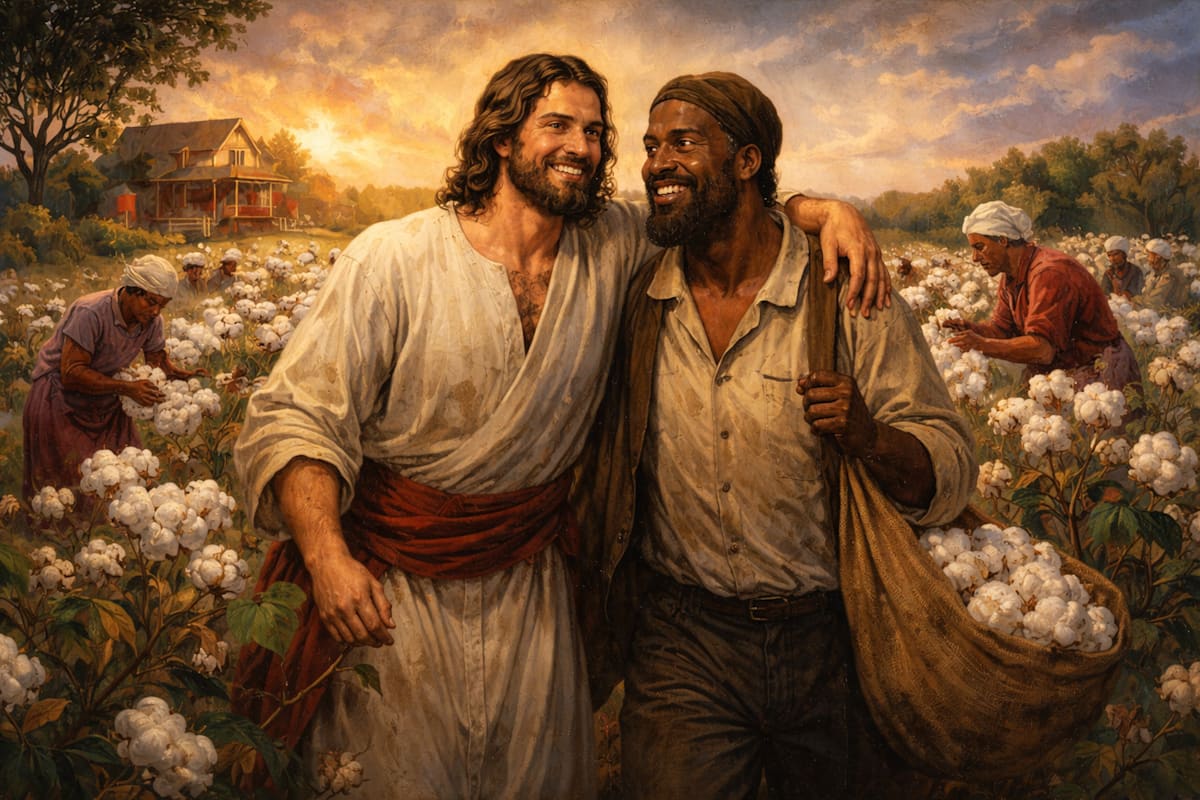

“Brother Jesus” – The Sibling the Slave Block Could Not Sell

In the "Invisible Institution" of the enslaved, the title "Lord" often felt distant, echoing the terminology of the master. Instead, the quarters whispered the name "Brother Jesus." This was not merely sentimental; it was a deliberate survival tactic against a system that systematically targeted biological siblings. Brothers were prime field hands, designated by the auctioneer as "assets" to be sold first, farthest, and fastest.

To name Jesus as "brother" was to claim a kinsperson who could never be sold, whipped, or bred for profit. While a "Lord" might sit on a throne, a "Brother" shared the lash marks and walked the rows of cotton. In the hush harbors, Mark 3:35 was received as an adoption decree: the slave quarters were no longer a collection of laborers, but a family the auction block could never touch.

The Underground Railroad as a Liturgy of Liberation

The Underground Railroad was far more than a secret route; it was the largest chosen-family network in American history, where Mark 3:35 functioned as the literal password for survival. This was a covenantal geography where strangers became "mother" or "sister" overnight through a shared commitment to the will of God—which, in this context, was the pursuit of freedom.

Safe houses, such as those run by Rev. John Rankin, utilized the liturgy of the Railroad to identify "passengers" as family. Rankin’s surviving ledgers record fugitives not as "runaways," but as "Brother Amos" or "Sister Ruth." This network, animated by the "othermothering" of figures like Harriet Tubman, proved that when the state weaponized the family tree, the Spirit could graft a new one from the bones of the old.

The “Church-Cousin” System and the Court of the Holy Ghost

During the Great Migration, six million Black refugees fled the Jim Crow South, arriving in northern cities with nothing but an address scribbled on a scrap of paper. One such address was "43rd and South Parkway" in Chicago—the home of Mother Johnson. These "Church Mothers" and "Church Cousins" provided a sophisticated economic and social safety net at a time when the American legal system denied Black citizens standing.

These titles were recognized in the "Court of the Holy Ghost," a legal alternative for a people who found no justice in the courts of men. When a newcomer was welcomed by Mother Johnson, they were not "clients" of a social service; they were family. This "church-cousin" system ensured that refugees were caught by chosen kinship before they hit the ground, providing mattresses, meals, and job leads as acts of covenantal obligation.

The Gospel in Ten-Inch Heels: Ballroom Houses as Sacred Space

In the late 20th century, the "Ballroom House" system emerged as a potent expression of "Womanist Queer Theology." When biological families "slammed the door" on queer youth, House Mothers like Crystal LaBeija performed a form of salvation through adoption. Amid the strobe-lit runways and the bass thumping like a second heartbeat, the ballroom did not abandon Christianity; it relocated it to where it was most needed.

House parents acted as "othermothers"—a concept defined by Patricia Hill Collins—exercising an authority grounded in survival. The theological heart of this movement was captured in the House of LaBeija’s own declaration:

"Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother. And tonight, honey, we doin’ God’s will in ten-inch heels!"

These houses were not social clubs; they were ecclesial structures that proved chosen kinship can be theologically superior to biological kinship when biology is used as a weapon.

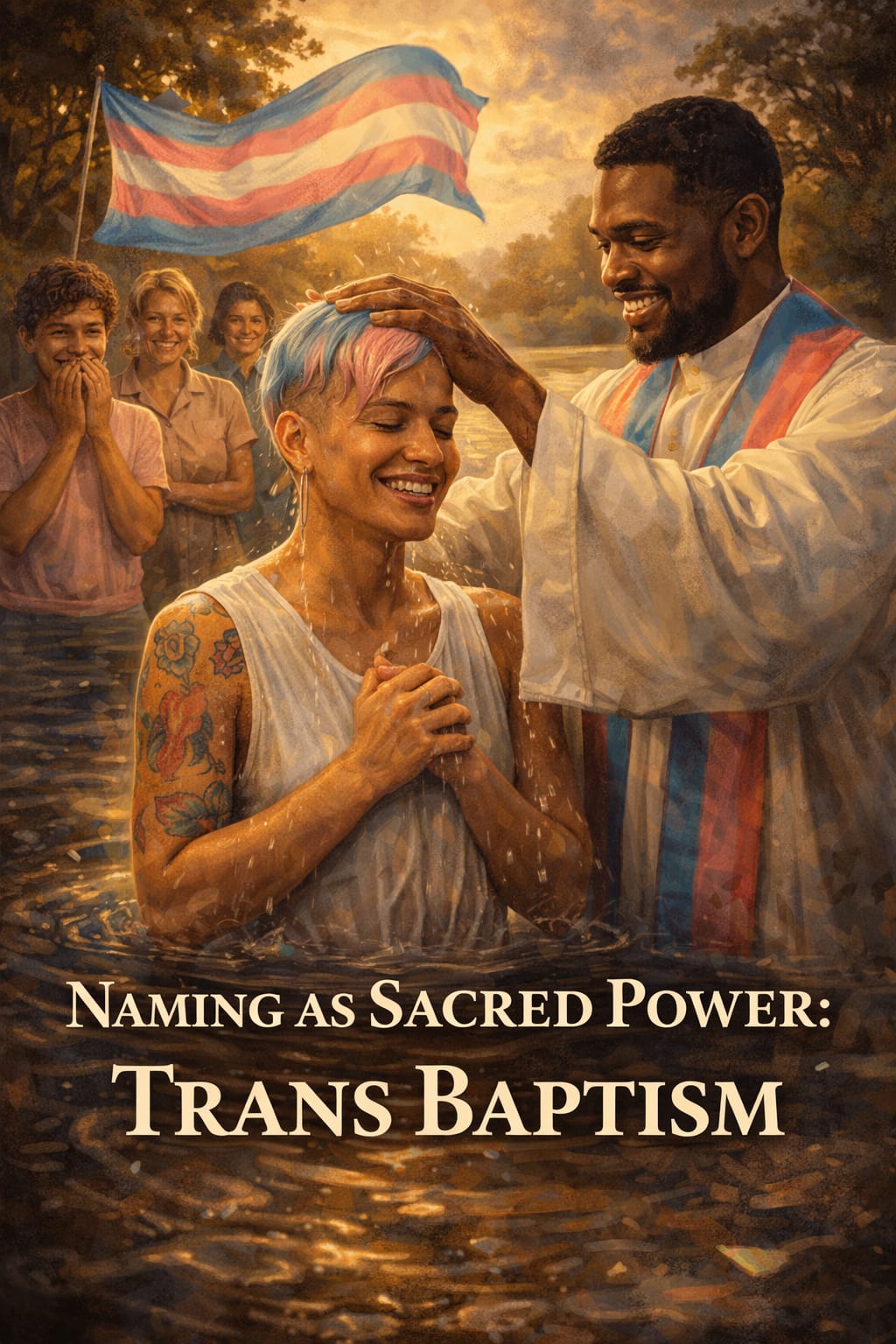

Naming as Sacred Power: Trans Baptism and the Future of Kinship

Today, the 400-year arc of Black family-making continues through the sacred power of naming. Just as Jesus renamed Simon to Peter, contemporary trans and non-binary believers, such as Zion Amari Jordan, use the waters of baptism to affirm their chosen names. In this "digital religion" era, platforms like TikTok host the "My Church Cousin Challenge," where thousands of users affirm that "doing the will of God" is the only valid criterion for family.

Within this framework, "deadnaming" is seen as a profound theological violation—a refusal to recognize the new identity Christ has bestowed. For these believers, the church's role is to honor the name God has given the individual, rather than the name on a birth certificate, prioritizing the covenant of the Spirit over the accident of the flesh.

A Seat at the Table

The history of Black Christian life is a testimony that challenges the contemporary church to move beyond "bio-centric" and heteronormative assumptions. The "unfinished work" of theology is to recognize that adoption, foster care, and queer chosen kinship are not "alternative" families, but the primary enactment of the Gospel. From the auction block to the ballroom floor, the message remains the same: if the church is to be the body of Christ, it must be a family flexible enough to catch those whom biological structures discard.

Is the modern church ready to catch up to the radical kinship modeled by the enslaved and the marginalized? The seat is already saved, and the names are already spoken. Blood may fail, but chosen family never will.