There is a uniquely human agony in crying out in pain and being met with silence. It is the grief that echoes in the hollow space where a prayer for answers used to be.

This experience is one of the most profound challenges to faith, and its rawest scriptural expression is found in the book of Lamentations.

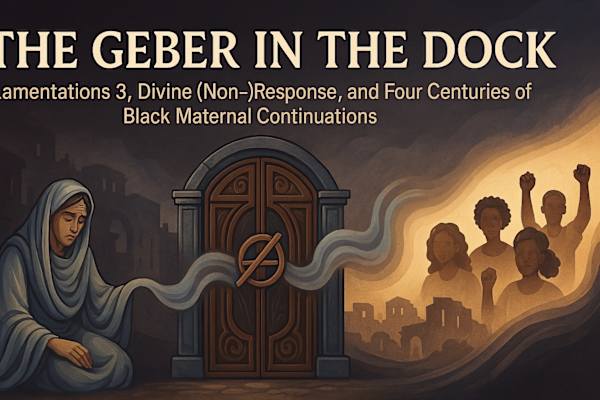

The book is a portrait of devastation, a city in ruins, and a people prosecuting God for their suffering. It stages an unresolved maternal lawsuit, a courtroom drama where the violated body of a nation is presented as evidence and God is placed in the dock.

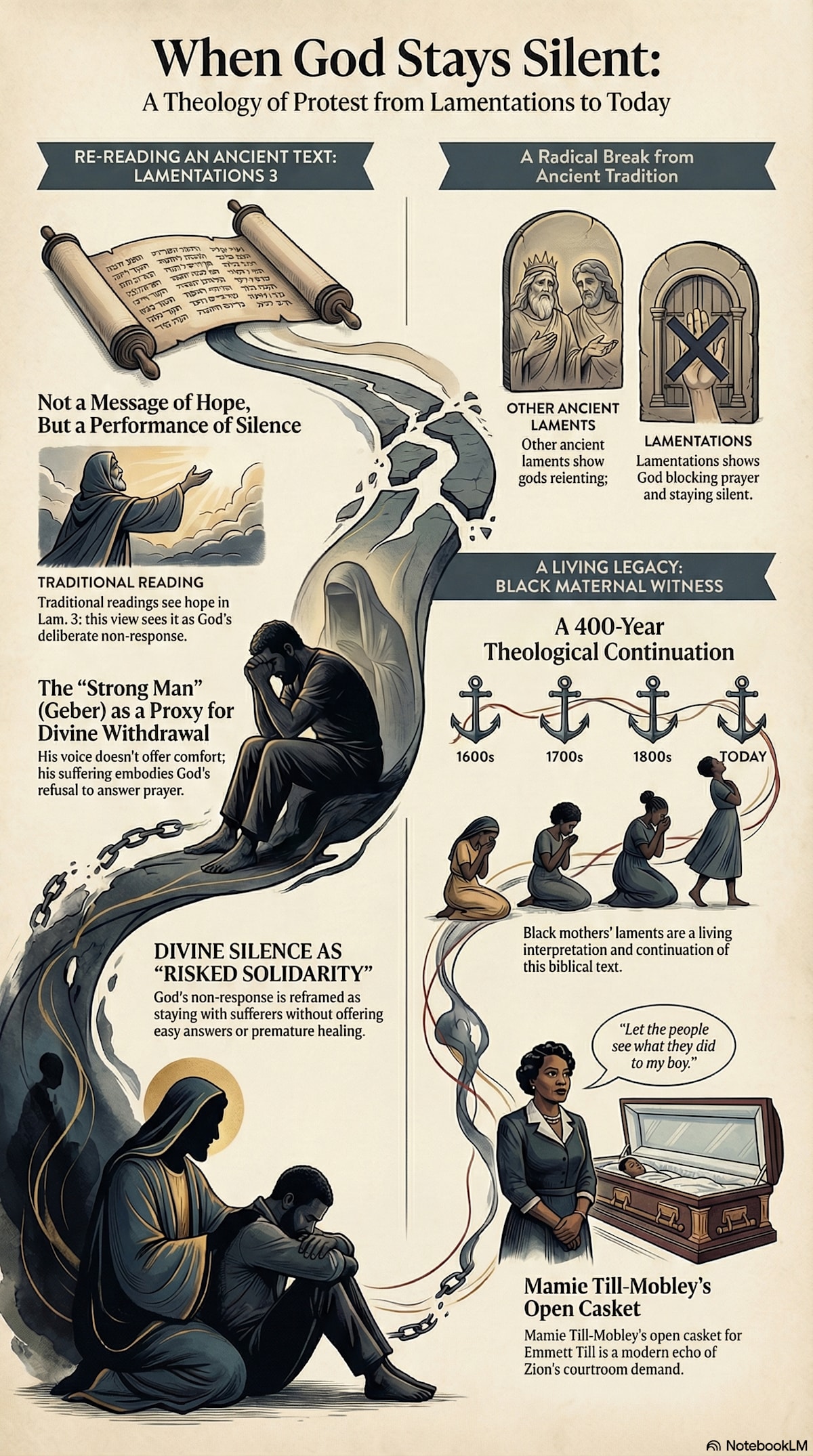

But what if the point of the book’s central chapter isn’t to provide a verdict, but to explore the meaning of divine silence itself? What if that silence is not absence, but a deliberate, active, and unsettling divine posture?

A radical reading of this ancient text reveals that God’s refusal to answer is not a failure of hope, but the very place where a more daring form of solidarity is forged, one that has urgent lessons for our own struggles for justice.

The "Hopeful" Center of the Bible's Saddest Book Is Really About God's Silence

It is a common misconception that Chapter 3 of Lamentations is a hopeful interlude in an otherwise bleak book. Readers often cling to verses like “The steadfast love of the LORD never ceases” as a moment of relief. But the literary and theological structure tells a different, more challenging story.

The chapter is voiced by a figure known as the geber, or “strong man.” His testimony is not a comforting message sent from God. Instead, his speech performs God’s deliberate non-response to the cries for help in the preceding chapters.

The chapter’s very form, a triple acrostic where the Hebrew alphabet repeats three times, reinforces this. As the source text puts it, “The tripled alphabet does not impose order on chaos; it multiplies it.

Trauma is not contained but proliferated. The text stutters under the weight of divine silence.” The apparent pivot to hope in verses 21-39 is structurally undercut and swallowed by the raw pleas for vengeance that follow it. The hope is not a resolution; it is overwhelmed by unrelieved accusation.

This performance of divine silence culminates in one of the Bible’s most chilling verses, which describes God’s posture not as passive distance but as active obstruction:

You have wrapped yourself with a cloud so that no prayer can pass through.

This cloud is an anti-theophany, a terrifying inversion of the cloud that revealed God’s presence at Sinai. Here, the cloud does not reveal; it obstructs. This is the heart of the chapter’s counter-intuitive argument: in the face of immense suffering, God’s response is not an answer or a rescue, but an intentional, resounding silence.

Unlike Other Ancient Laments, This One Radically Breaks the Rules

To grasp how theologically innovative Lamentations is, we must look at its ancient neighbors. In other Ancient Near Eastern cultures, laments were ritual mechanisms designed to secure a divine response. The formula was clear: destruction leads to lament, which leads to divine relenting, which leads to restoration. These rituals were performed in a world with intact temples—the architectural and cultic systems for getting an answer were still in place.

The most famous example is the Lament for Ur, where the goddess Ningal passionately pleads with the high gods to spare her city. Her intercession is effective. The gods are moved, and the city is decreed to be rebuilt. But Lamentations emerges from a world in which the temple has been destroyed. The very structure that once mediated divine response has collapsed.

This is why the biblical text shatters the ANE formula. In chapters 1 and 2, Daughter Zion pleads just like Ningal, presenting the executed bodies of her children as evidence and demanding that God look. But her pleas are met with the profound divine silence embodied by the geber in chapter 3. God refuses to be moved by the established rituals. This is a radical theological innovation that forces the reader to sit with an unresolved accusation, refusing the easy comfort of a guaranteed divine response.

The Cries of Black Mothers Are a 2,600-Year-Old Biblical Protest

The unresolved maternal lawsuit of Daughter Zion finds its most powerful continuation in the public laments of Black mothers confronting the racialized crucifixion of their children. This connection is not a simple comparison; it is what scholars call a "lived exegesis," a theological continuation of the biblical text in the modern world.

When Lesley McSpadden stood over the body of her son, Michael Brown, in Ferguson, she asked a question that echoes across millennia:

“They still don’t have an answer for me. Where was God when my baby was lying there?”

Her cry was not one of resignation but of accusation, a forensic summons directed at both state power and divine silence. It resonates with the testimony of Sybrina Fulton, mother of Trayvon Martin, who said of her own prayers, “it was like talking to a wall. The quiet was the loudest thing.” Decades earlier, Mamie Till-Bradley insisted on an open casket for her murdered son, Emmett, so the world could “see what they did to my boy.” Her demand to exhibit the mutilated body of her child was a modern enactment of Zion’s ancient command: "See, O LORD, and look!"

This reading, grounded in the work of Womanist theologians like Delores Williams and Emilie Townes, understands this tradition of protest, from the spirituals of enslaved people to the testimonies of the Mothers of the Movement, as continuing the biblical posture of Lamentations. It is a tradition that holds both human empire and divine silence to account, refusing the theological violence of demanding premature closure.

True Hope Isn't an Answer—It's the Refusal to Stop Asking the Question

This reading of Lamentations forces us to redefine hope. Hope, in this book, is not optimism. It is not the expectation of a quick resolution or the refusal of cheap grace.

Instead, hope is the "embodied grammar of unrelieved grief." It is the active, faithful discipline of staying in the maternal courtroom, exhibiting the evidence of suffering, and insisting on accountability. Hope is a forensic action, a form of covenantal fidelity that dares God to remain accountable. It is the refusal to adjourn the trial.

In this framework, divine silence is not abandonment. It is "risked solidarity" God choosing to remain implicated in the world’s suffering, to stay in the dock with the accused, rather than resolving it from a safe, divine distance. This redefines hope not as a passive feeling, but as a courageous act of protest and fidelity in the face of overwhelming pain.

The ancient text of Lamentations offers a profound grammar for confronting suffering today. It teaches us to value persistent, unresolved lament over the false comfort of premature closure. It gives us a language for when God seems silent, reframing that silence not as absence, but as a space where solidarity is forged and true hope is practiced as a demanding discipline.

In a world demanding premature healing, what does it mean to practice a hope that refuses to leave the scene of the crime?